In the summer of 1816 at Villa Diodati took place an encounter that marked an inflection point in fantasy and science fiction literature, because in one of the night meetings of these days the literary work Frankenstein, Or The Modern Prometheus, written by Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851) was born. In this new post I'm devoting to the artificial beings in literature and roleplaying games I will tlk about the mosnter and its creator and will see some examples of how it has influenced the fiction of the following years.

Year without Summer and Villa Diodati

|

|

File:Tambora ashfall 1815.svg - Wikimedia Commons

(CC BY-SA 3.0) |

|

|

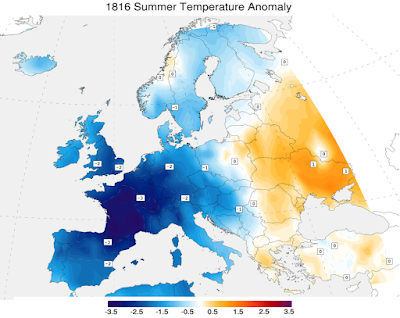

File:1816 summer.png - Wikimedia Commons

(CC BY-SA 3.0) |

1816, also known as The Year Without a Summer by the effects of the eruption of Tambora volcano in Indonesia the previous year and the low solar activity period known as Dalton Minimum (1790 – 1830), was a disaster regarding climatology, with an important drop in temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere and other climatology aberrations taking place, affecting Northern America, Western Europe, Tibet and China, giving rise to important harvesting losses causing a widespread hunger, epidemic, unrest and rebellions due to lack of food.

|

|

|

Villa Diodati

(Public Domain) |

Portrait of Lord Byron painted in 1813 by Thomas Philips (Public Domain) |

It was during the summer of such a dire year that the meeting concerning us took place thanks to George Gordon Byron (1788 – 1824), better known as Lord Byron, who was the pinnacle of the British romantic movement and heroe of the Greek War of Independence (1821 – 1829).

.jpg)

|

|

|

Portrait of Annabella Byron painted in 1812 by Charles Hayter (Public Domain) |

Portrait of Ada Lovelace possibly painted by Alfred Edward Chalon in 1840 (Public Domain) |

|

.jpg)

|

|

Portrait of the Obituary of Charles Babbage, Illustrated London News (4 November 1871), by Thomas Dewell Scott (Public Domain) |

Babbage's Analytical Engine (1834-1871) (CC BY-SA 2.0) |

The poet rented Villa Diodati from 10 June to 1 November to spend a time away from England, fleeing debts and the scandal caused by his divorce from Anna Isabella Milbanke (1792 – 1860) after the birth of his daughter, the future writer and mathematician Ada Lovelace (1815 – 1852), considered by many as the first programmer by her work in the analytical engine by Charles Babbage (1791 – 1871).

Anna Isabella, best known as Lady Byron, besides having an education emphasizing the study of astronomy and mathematics was also a very religious person (leading her to participate in social causes like the abolition of slavery in the United Kingdom), got scared by the continual drunkennes of the poet, his open hostility to her and the way he managed his economy. The situation got worse when she began to suspect that he mantained an incestuous relationship with his half-sister, Augusta Maria Leigh (1783 – 1851). All these issues took her to think her husband had gone mad and ask for the divorce (although this didn't prevent her to be obsessed with her husband until the end of her life).

|

|

|

Portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, painted in 1840 by Richard Rothwell (Public Domain) |

Portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley, painted in 1819 by Alfred Clint (Public Domain) |

|

|

|

Portrait of Augusta Maria Leigh, painted in 1817 by James Holmes (Public Domain) |

Portrait of Claire Clairmont, painted in 1819 by Amelia Curran (Public Domain) |

Mary reached Geneva 14 may with her future husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822), their son and her half-sister, Claire Clairmont (1798 – 1879), pregnant by Lord Byron after an encounter with him at the beginning of the year. During these first months they have traveled France, devastated by the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813 – 1814) against Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821), a journey that had a lasting impact on Mary, as recollected in the log of the journey wtitten with Percy:

We now approached scenes that reminded us of what we had nearly forgotten, that France had lately been the country in which great and extraordinary events had taken place. Nogent, a town we entered about noon the following day, had been entirely desolated by the Cossacs. Nothing could be more entire than the ruin which these barbarians had spread as they advanced; perhaps they remembered Moscow and the destruction of the Russian villages; but we were now in France, and the distress of the inhabitants, whose houses had been burned, their cattle killed, and all their wealth destroyed, has given a sting to my detestation of war, which none can feel who have not travelled through a country pillaged and wasted by this plague, which, in his pride, man inflicts upon his fellow.

History of a Six Weeks’ Tour through a part of France, Switzerland, Germany and Holland (1817)

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

A ghost story

After meeting up with Lord Byron in 25 May John William Polidori (1795 – 1821), also a writer and the personal doctor of the poet, joined them. In these days, which were notably rainy, they spent the time reading, boating in the lake and mantaining long conversations until daybreak, until one night of June (surely the one of the 15th), after reading the Fantasmagoriana anthology of short tales about spectres in the firelight, Lord Byron proposed every one of them to write a ghost story, as the authoress explains in the preface of her work:

"We will each write a ghost story," said Lord Byron; and his proposition was acceded to. There were four of us. The noble author began a tale, a fragment of which he printed at the end of his poem of Mazeppa. Shelley, more apt to embody ideas and sentiments in the radiance of brilliant imagery, and in the music of the most melodious verse that adorns our language, than to invent the machinery of a story, commenced one founded on the experiences of his early life. Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady, who was so punished for peeping through a key-hole—what to see I forget—something very shocking and wrong of course; but when she was reduced to a worse condition than the renowned Tom of Coventry, he did not know what to do with her, and was obliged to despatch her to the tomb of the Capulets, the only place for which she was fitted. The illustrious poets also, annoyed by the platitude of prose, speedily relinquished their uncongenial task.

I busied myself to think of a story,—a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror—one to make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be unworthy of its name. I thought and pondered—vainly. I felt that blank incapability of invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our anxious invocations. Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.

Frankenstein:

Or,

The modern prometheus.

Preface

(1831 Edition)

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

After some days in which Mary found impossible to have an idea for her tale, the groups' nocturnal talkings ended focusing in the nature of the origins of life and the possibility of corpses' reanimation:

Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. They talked of the experiments of Dr. Darwin, (I speak not of what the Doctor really did, or said that he did, but, as more to my purpose, of what was then spoken of as having been done by him,) who preserved a piece of vermicelli in a glass case, till by some extraordinary means it began to move with voluntary motion. Not thus, after all, would life be given. Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.

Frankenstein:

Or,

The modern prometheus.

Preface

(1831 Edition)

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

This conversation was, of course, what provoked that night Mary having the nightmre that began all of it:

Night waned upon this talk, and even the witching hour had gone by, before we retired to rest. When I placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness far beyond the usual bounds of reverie. I saw—with shut eyes, but acute mental vision,—I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handywork, horror-stricken. He would hope that, left to itself, the slight spark of life which he had communicated would fade; that this thing, which had received such imperfect animation, would subside into dead matter; and he might sleep in the belief that the silence of the grave would quench for ever the transient existence of the hideous corpse which he had looked upon as the cradle of life. He sleeps; but he is awakened; he opens his eyes; behold the horrid thing stands at his bedside, opening his curtains, and looking on him with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes.

I opened mine in terror. The idea so possessed my mind, that a thrill of fear ran through me, and I wished to exchange the ghastly image of my fancy for the realities around. I see them still; the very room, the dark parquet, the closed shutters, with the moonlight struggling through, and the sense I had that the glassy lake and white high Alps were beyond. I could not so easily get rid of my hideous phantom; still it haunted me. I must try to think of something else. I recurred to my ghost story,—my tiresome unlucky ghost story! O! if I could only contrive one which would frighten my reader as I myself had been frightened that night!

Swift as light and as cheering was the idea that broke in upon me. "I have found it! What terrified me will terrify others; and I need only describe the spectre which had haunted my midnight pillow." On the morrow I announced that I had thought of a story. I began that day with the words, It was on a dreary night of November, making only a transcript of the grim terrors of my waking dream.

Frankenstein:

Or,

The modern prometheus.

Preface

(1831 Edition)

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

A possible inspiration: The gallows of Tyburn and glvanism

|

|

Illustration of the permanent gallows at Tyburn (probably 1680) (Public Domain) |

Reaching this point the question arises about the events inspiring Mary Shelley this so vivid and sinister vision.

First of all the reference to corpses has to be considered, a thing which shouldn't surprise us given that the authoress was born in the London district of Somers Town (nowadays Camden), famous among other reasons for the executions carried out at Tyburn, something that surely got stucked in folk memories.

Although there had been many execution sites in the capital, like the famous Tower of London, a great number of executions were carried out at the Tyburn crossroad from 12th century to the end of 18th century, often with a lot of viewers. Methods used were varied and gave rise to scenes which certainly must have been impressive, like the first dismemberment, carried out in 1241 or the hanging at the same time of 24 prisoners (23 men and a woman) in 1649. At that it's also worth commenting the attitude of the witnesses, for whom this was a show worth beholding, or those believing that the corpses of the recently executed had healing properties and paid the hangmen to allow them to touch the corpses. At the executions also used to assist family and friends of the convicts, trying to end the suffering of the hanged pulling their legs or brawling with the surgeons' assistants to prevent them to take away their kin's corpses and so give them a proper burial.

If you want to know more about the history of the place and the execution carried out there you may read The Proceedings of Old Bailey and Capital Punishment U.K..

|

|

|

Alessandro Volta

(Public Domain) |

Luigi Galvani

(Public Domain) |

|

.jpg)

|

|

Portrait of Giovanni Aldini (1829) (Public Domain) |

Portrait of Erasmus Darwin, painted in 1792 by Joseph Wright of Derby (Public Domain) |

Regarding the possibility to reanimate a body using electricity, Mary Shelley was referring to investigations about galvanism carried out by Alessandro Volta (1745 – 1827) (inventor of the voltaic pile in 1799) and Luigi Galvani (1737 – 1798) about the generation of electricity by means of chemical reactions as well as muscular tissue contraction/convulsion in biological beings when coming in contact with electrical current, as he discovered through experimentation carried out during 11 years stimulating the sciatic nerve of frog legs, as can be seen in the following recreation of the experiment:

After the decease of Galvani his research was kept up by his nephew, Giovanni Aldini (1762 – 1834), famous for the public demonstration carried out in London animating part of the corpse of criminal George Forster, executed at Newgate Prison at January 18th 1803:

On the first application of the process to the face, the jaws of the deceased criminal began to quiver, and the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.

The Newgate Calendar – George Foster

Executed at Newgate, 18th of January, 1803, for the Murder of his Wife and Child,by drowning them in the Paddington Canal;

with a Curious Account of Galvanic Experiments on his Body

Sparks of life | Research | The Guardian

The demonstration by Aldini probably was known by Mary Shelley, isn't it?

Other scientists of the era experimenting with galvanism and probably having a certain degree of influence in the genesis of the book were the naturalist James Lind (1736 – 1812) (Percy Shelley's tutor at Eton College during 1809) and Erasmus Darwin (1731 – 1802), physician and naturalist mentioned in the introduction to the novel in the 1831 edition as you have read before, who was also the paternal grandfather of Charles Darwin, author of the Evolution Theory.

The birth of the novel and of genre

Days spent in Villa Diodati resulted in a work that without doubt changed the fantasy genre, because Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus is considered by authors like Brian Aldiss (1925 – 2017) as the book initiating the modern science fiction.

|

|

|

Page title of the first volume of Frankenstein, First Edition (1818) (Public Domain) |

Frontispiece of Frankenstein, Third Edition (1831), by Theodore Von Holst (Public Domain) |

The book had three editions during the autoress' life: 1818 (published in three volumes anonimously), 1823 (published in two volumes and crediting Mary Shelley as the authoress) and 1831 (one volume only and first "popular" edition, throughly checked by the authoress and including a preface where she explains in a somewhat embelished the genesis of the story), and had always enjoyed a great reader acceptance in spite of some criticisms, like the one appearing in The British Critic, N.S., 9 (April 1818), where the authoress was criticised by the fact of being a woman:

"The writer of it is, we understand, a female; this is an aggravation of that which is the prevailing fault of the novel; but if our authoress can forget the gentleness of her sex, it is no reason why we should; and we shall therefore dismiss the novel without further comment".

Frankenstein was planned as an epistolary novel (that is developed through correspondence of the main characters), taking place in the 18th century and starting with the account of captain Robert Walton, a failed writer becoming a polar explorer, sent to his sister explaining how, during the course of his expedition, found a man called Victor Frankenstein in poor physical condition and how the man explained the circumstances taking him so far in his quest, no other than chase the monster created by himself emulating the Prometheus myth (and from here comes the sub-title of the work, excluded from later editions). The monster torments him, rightfully holding him to be responsible of his miserable existence and being not able of offering him a full and normal life as anyone, what will lead hime to undertake his revenge.

More influence in the fantasy genre

|

_-_Vampyre,_1819.jpg)

|

|

Portrait of John William Polidori, painted by F.G. Gainsford (Public Domain) |

Title page of The Vampyre (1819) (Public Domain) |

Without doubt those days at Villa Diodti were certainly prolific and ended influencing the later fantasy genre.

An example of this is the short novel The Vampyre, written by Polidori in 1819 and considered as one of the first modern works of romantic vampire genre, based in Balcanic legends Lord Byron explained to the doctor during those days and the unfinished tale Fragment of a novel, written by the aristocrat the same year (something that surely first attributed the work to Lord Byron although he repeatedly negated it and Polidori wrote a letter to the editor explaining that, although the base of the book was clearly due to Lord Byron, the development of the characters had been his).

Other examples of the imprint of the work of Mary Shelley is Frankenstein Unbound, a science fiction novel written by Brian Aldiss in 1973 taking as a background the original work and adapted to the big screen in 1990 by Roger Corman, as well as other works treating one way or another the creation of artificial life as will be seen in future chapters of this series.

Adaptations to other media

Of course a so famous work had seen many adaptations in other media and a lot of works influenced by the events that happened at Villa Diodati had been created.

Beginning with cinematography and television the following ones could be highlighted:

Frankenstein (1910)

Wikipedia

IMDb

Library of Congress

Internet Archive

Frankenstein (1931)

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

Young Frankenstein (1974)

Gothic (1986)

Remando al Viento (1988)

Frankenstein Unbound (1990)

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1994)

Frankenstein (2004)

|

|

Bernie Wrightson's Frankenstein

(Fair Use) |

And taking advantage of the character being now in the public domain he also have had a great number of comicbook adaptations (many of them of a somewhat questionable quality or quite simple), so without a doubt the star is the adaptation drawn by Berni Wrightson en 1983.

If you are interested to know more about other representations in the so called "popular culture" you may read these articles of the English language wikipedia (Frankenstein in popular culture - Wikipedia | List of films featuring Frankenstein's monster - Wikipedia) and the website FrankensteinFilms.

Frankenstein's Monster in roleplaying games

|

|

.jpg)

|

|

Ravenloft (module) (Fair Use) |

Ravenloft: Realm of Terror (supplement) (Fair Use) |

Adam's Wrath (adventure) (Fair Use) |

Having reached roleplaying games it's easy to think that the most suitable rulesets to represent Frankenstein's Monster would be those designed to represent gothic fantasies (including any version of Dungeons & Dragons or similar games), although you will see there are other interesting options.

First we may think about the meat golem, a creature similar to the Monster which can be found in Dungeons & Dragons 5ed in the following versions:

And fan creations:

- D&D 5E - Epic Monsters: Frankenstein's Monster | EN World Tabletop RPG News & Reviews

- Frankenstein (5e Race) - D&D Wiki

(although we must not forget the in the Ravenloft campaign environment also exists a similar character, introduced in the supplement Realm of Terror and the adventure Adam’s Wrath).

|

|

|

Dark Harvest: Legacy of Frankenstein

(Fair Use) |

Dark Harvest: Resistance

(Fair Use) |

On the other hand you may also be interested in the game Dark Harvest: Legacy of Frankenstein, a roleplaying game compatible with Victoriana 2nd edition showing us an alternative world where Victor Frankenstein don't doubt to take advantage of his scientific knowledge for his own benefit no matter the consequences. The basic manual can be freely downloaded from DriveThruRPG and Resistance, the first supplement, can be obtained as pay-what-you-want”.

|

|

|

1800: El Ocaso de la Humanidad

(Fair Use) |

1800: Codex Gigas

(Fair Use) |

And speaking of gothic and dark imagery you may also be interested in 1800: El Ocaso de la Humanidad and its supplement 1800: Codex Gigas. Both works were financed with crowdfundings in 2018 and 2019 and portray an uchronic 19th century showing a demonic invasion of the world mixed with the aparition of steampunk and teslapunk technology. Although in the game there isn't the creature as such, the supplement 1800: Codex Gigas offers enough information to create it (and the game is offered under the CC BY-NC-SA license, so fans may create free derived contents). Authors put the basic manual as a free download at MEGA last 29 October communicating it through Twitter (the same publication through Nitter) and if you want to support them both works can still be found in physical format in some shops in Spain or as pdf for sale at Lulu:

|

|

|

DC Heroes (Third Edition)

(Fair Use) |

Blood of Heroes

(Fair Use) |

To finish this section devoted to roleplaying games you may also be interested to read Frankenstein's Monster stats appearing at Writeups.org, a fan website devoted to offer contents for the roleplaying games DC Heroes (with editions in 1985, 1989 and 1993) and Blood Heroes (edited in 1998), both used the Mayfair Exponential Game System and are already out of print for years. If you want more information about these games and the system you may also read the following links:

- La entrada sobre DC Heroes and Blood of Heroes en TV Tropes

- Writeups.org

- Blood of Heroes RPG « ICEWEBRING

- DC Heroes RPG Rules

- DC Heroes RPG

- Mayfair DC Heroes Character Database

- Siskoid's Collection - Character Index

- Home | Marvel Superheroes - The MEGS Experience

Public Domain: Where you may reaad works of Mary Shelley

|

|

| Mary Shelley - Frankenstein | Mary Shelley - The Last Man |

To finish this third installment of the series devoted to artificial beings only rests to show where you can legally download the texts of the works of Mary Shelley because these are under public domain.

To got them you only have to consult these links:

By the way, I don't know if you knew that Mary Shelley published in 1826 the distopic novel The Last Man, where she described how the Humanity gets extinguished at the end of the 21st century by a pandemic... Badly received at the time, it was recovered in the 1960's decade and it makes you think...

This entry it's also available in the following languages:

Castellano Català

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario